Yoshiyuki Kohei

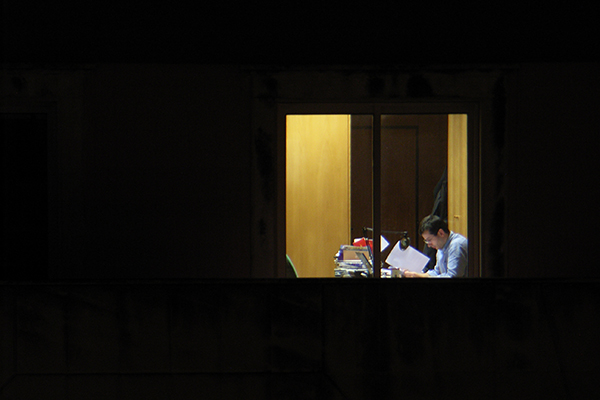

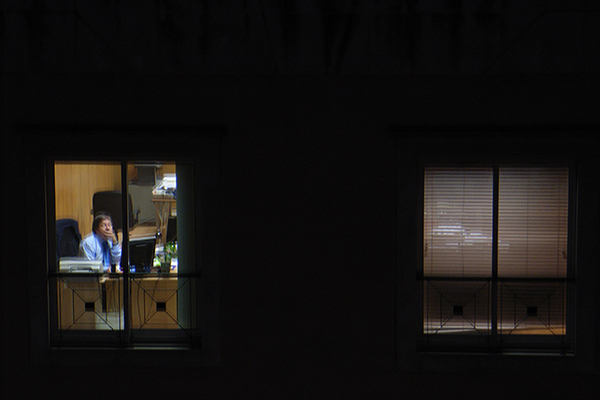

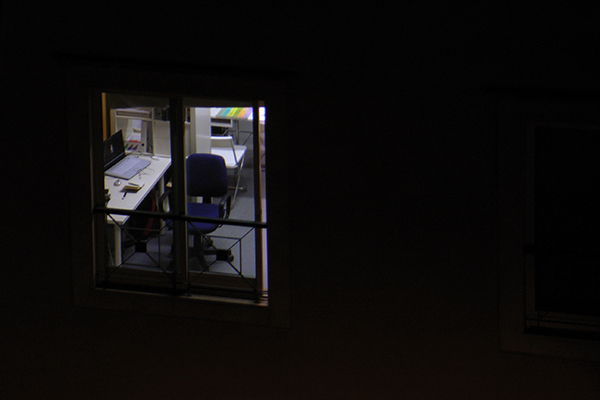

Mr. Yoshiyuki was a young commercial photographer in Tokyo in the early 1970s when he and a colleague walked through Chuo Park in Shinjuku one night. He noticed a couple on the ground, and then one man creeping toward them, followed by another.

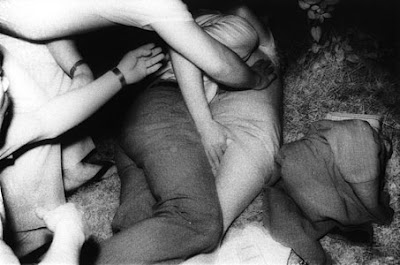

“I had my camera, but it was dark,” he told the photographer Nobuyoshi Araki in a 1979 interview for a Japanese publication. Researching the technology in the era before infrared flash units, he found that Kodak made infrared flashbulbs. Mr. Yoshiyuki returned to the park, and to two others in Tokyo, through the ’70s. He photographed heterosexual and homosexual couples engaged in sexual activity and the peeping toms who stalked them.

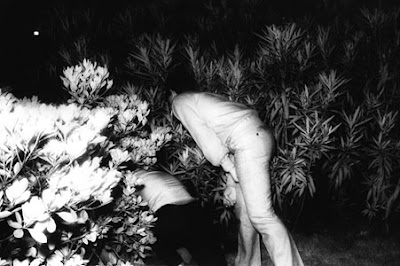

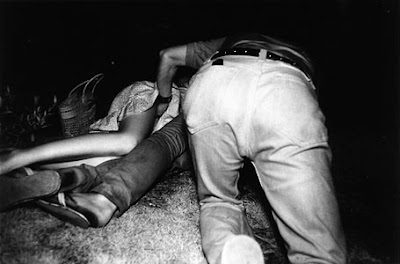

“Before taking those pictures, I visited the parks for about six months without shooting them,” Mr. Yoshiyuki wrote recently by e-mail, through an interpreter. “I just went there to become a friend of the voyeurs. To photograph the voyeurs, I needed to be considered one of them. I behaved like I had the same interest as the voyeurs, but I was equipped with a small camera. My intention was to capture what happened in the parks, so I was not a real ‘voyeur’ like them. But I think, in a way, the act of taking photographs itself is voyeuristic somehow. So I may be a voyeur, because I am a photographer.”

Mr. Yoshiyuki’s photographic activity was undetected because of the darkness; the flash of the infrared bulbs has been likened to the lights of a passing car.

“The couples were not aware of the voyeurs in most cases,” he wrote. “The voyeurs try to look at the couple from a distance in the beginning, then slowly approach toward the couple behind the bushes, and from the blind spots of the couple they try to come as close as possible, and finally peep from a very close distance. But sometimes there are the voyeurs who try to touch the woman, and gradually escalating — then trouble would happen.”

Mais informação aqui

Rear Window - James Stewart

Rear Window - James Stewart

Rear Window

Rear Window

| Rear Window | |

|---|---|

Movie Poster | |

| Directed by | Alfred Hitchcock |

| Produced by | Uncredited: Alfred Hitchcock |

| Written by | Short story: Cornell Woolrich "It Had to Be Murder" Screenplay John Michael Hayes |

| Starring | James Stewart Grace Kelly Thelma Ritter Wendell Corey Raymond Burr Judith Evelyn |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

| Running time | 112 min. |

Rear Window is a 1954 film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, based on Cornell Woolrich's 1942 short story It Had to Be Murder. It stars James Stewart as photojournalist L. B. Jefferies, Grace Kelly as his fashion model girlfriend Lisa Carol Fremont, and Raymond Burr as the suspected killer, Lars Thorwald. The film combines its main theme of a murder mystery with a critical examination of the ethics of marriage and voyeurism.

The film is considered by many film goers, critics and scholars to be one of Hitchcock's best and most thrilling pictures.[1] Rear Window is one of several films directed by Hitchcock originally released by Paramount Pictures, that were acquired by Universal Studios in later years.

Hitchcock's cameo

Alfred Hitchcock appears briefly onscreen in the film as the man winding the clock in the songwriter's apartment as the songwriter is performing the piece that he had been working on during the course of the film.

Analysis

Hitchcock's fans and film scholars have taken particular interest in the way the relationship between Jeff and Lisa can be compared to the lives of the neighbors they are spying upon. Many of these points are considered in Tania Modleski's feminist theory book, The Women Who Knew Too Much. (ISBN 0-415-97362-7)[2]

- Thorwald and his wife are a reversal of Jeff and Lisa (Thorwald looks after his invalid wife just as Lisa looks after the invalid Jeff). However, Thorwald's hatred of his nagging wife mirrors Jeff's arguments with Lisa.

- The newlywed couple initially seem perfect for each other (they spend nearly the entire movie in their bedroom with the blinds drawn), but at the end we see that their marriage is in trouble and the wife begins to nag the husband. Similarly, Jeff is afraid of being 'tied down' by marriage to Lisa.

- The middle-aged couple with the dog seem content living at home. They have the kind of uneventful lifestyle that horrifies Jeff.

- The music composer and Miss Lonely Heart, the depressed spinster, lead frustrating lives, and at the end of the movie find comfort in each other (the composer's new tune draws Miss Lonely Heart away from suicide, and the composer thus finds value in his work). There is a subtle hint in this tale that Lisa and Jeff are meant for each other, despite his stubbornness. The piece the composer creates is called "Lisa's Theme" in the credits.

The movie invites speculation as to which of these paths Jefferies and Lisa will follow.

The characters themselves verbally point out a similarity between Lisa and Miss Torso (played by Georgine Darcy) - the scantily-clad ballet dancer who has all-male parties.

A thoughtful analysis of Rear Window can be found in John Fawell's book The Well-Made Film. Other analysis centers on the relationship between Jeff and the other side of the apartment block, seeing it as a symbolic relationship between spectator and screen. Film theorist Mary Ann Doane has made the argument that Jeff, representing the audience, becomes obsessed with the screen, where a collection of storylines are played out. This line of analysis has often followed a feminist approach to interpreting the film. It is Doane who, using Freudian analysis to claim women spectators of a film become "masculinized," pays close attention to Jeff's rather passive attitude to romance with the elegant Lisa, that is, until she crosses over from the spectator side to the screen, seeking out the wedding ring of Thorwald's murdered wife. It is only then that Jeff shows real passion for Lisa. In the climax, when he is pushed through the window (the screen), he has been forced to become part of the show.

Legacy

Brian De Palma paid homage to Rear Window with his movie Body Double (which also added touches of Hitchcock's Vertigo). The 2001 film Head Over Heels starring Freddie Prinze Jr., in which a young woman falls for a man she believes she saw commit a murder, closely follows the plot of Rear Window, as well as the 2007 film Disturbia - although in this film, there is no accident, and the suspect has no wife. Marcos Bernstein's The Other Side of The Street (2004) also makes a reference to Rear Window, albeit with a Brazilian twist. Many animated series, including Tiny Toon Adventures, Rocket Power, The Simpsons, Rocko's Modern Life, Home Movies, That ´70s Show and The Venture Bros. have paid homage to Rear Window in different ways. Robert Zemeckis' What Lies Beneath is another film that pays tribute to this film and other Hitchcock features. Woody Allen's Manhattan Murder Mystery, in which Allen and his wife suspect an elderly neighbor of murdering his wife and are forced to investigate for themselves when no one else takes their concerns seriously, could also be said to owe a debt to Rear Window.

This movie has been deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. The film was restored by the team of Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz for its 1999 limited theatrical re-release and the Collector's Edition DVD release.

The film received four Academy Award nominations: Best Director for Alfred Hitchcock, Best Screenplay for John Michael Hayes, Best Cinematography, Color for Robert Burks, Best Sound Recording for Loren L. Ryder, Paramount Pictures.

This film was ranked #14 on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills. It was ranked #48 on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition). To this day, the film gets a 100% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes.

Ownership of the copyright in Woolrich's original story was eventually litigated before the United States Supreme Court in Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207 (1990). The film was copyrighted in 1954 by Patron Inc. — a production company set up by Hitchcock and Stewart. As a result, Stewart and Hitchcock's estate became involved in the Supreme Court case.

The film was shot entirely at Paramount studios, including an enormous set on one of the soundstages, and employed the Technicolor process in use at the time. There was also careful use of sound, including natural sounds and music drifting across the apartment building courtyard to James Stewart's apartment. At one point, the voice of Bing Crosby can be heard singing "To See You Is to Love You" originally from the Paramount release Road to Bali (1952).

Hitchcock used famed designer Edith Head to design costumes in all of his Paramount films. (She continued to design costumes for his films when Hitchcock moved to MGM in 1959 and then to Universal in 1960 until the end of his career.) With Hitchcock's encouragement, Head designed especially "romantic" dresses for Grace Kelly.[3]

Rear Window - Grace Kelly, James Stewart

Rear Window - Grace Kelly, James Stewart

Rear Window - Still

Rear Window - Still

Blow-Up

Blowup

| Blowup | |

|---|---|

Blowup DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Produced by | Carlo Ponti |

| Written by | Michelangelo Antonioni Tonino Guerra Edward Bond (dialogues) |

| Starring | Vanessa Redgrave Sarah Miles David Hemmings |

| Music by | Herbie Hancock |

| Cinematography | Carlo Di Palma |

| Running time | 111 min |

Blowup (as in screen credits, also rendered as Blow-Up) is an award-winning 1966 British-Italian art film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and was that director's first English language film. It tells the story of a photographer's involvement with a murder case. The film was inspired by the short story "Las Babas del Diablo" ("The Droolings of the Devil") by Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar, and by the work, habits, and mannerisms of Swinging London photographer David Bailey.

Blowup stars David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave, Sarah Miles, John Castle, and Jane Birkin. The screenplay was written by Antonioni and Tonino Guerra, with the English dialogue being written by British playwright Edward Bond. The film was produced by Carlo Ponti, who had contracted Antonioni to make three English language films for MGM (the others were Zabriskie Point and The Passenger).

Synopsis

The story concerns a photographer (Hemmings) who may or may not have inadvertently preserved evidence of a murder, which may or may not involve a woman (Redgrave) who visits the photographer in his studio. As is typical with Antonioni films, the story does not follow a conventional narrative structure.

As a professional photographer, the main character mixes with the rich and famous in the London of the sixties. One day he chances upon two lovers in a park and takes photos of them. The woman of the couple pursues him, eventually finding his apartment and desperately trying to get the film. This leads the photographer to investigate the film, making blowups (enlargements) of the photos. This process seems to reveal a body, but the director uses the heavy film grain and black and white imagery to obscure the image. This drives the photographer to keep making blowups and try to find the truth. He does eventually find the body in the park, but this time, unfortunately and surprisingly, he is without his camera. He tries to get a friend to act as witness, but later the body is gone.

Ultimately, the film is about reality and how we perceive it or think we perceive it. This aspect is stressed by the final scene, one of many famous scenes in the film, when the photographer watches a mimed tennis match and, after a moment of amused hesitation, enters the mimes' own version of reality by picking up the invisible ball and throwing it back to the two players. A tight shot shows his continued watching of the match, and, suddenly, we even hear the ball being played back and forth. Another version of reality has been created. Then, at the very end, Hemmings, standing all alone in the green grass of the park, suddenly disappears, removed by his director, Antonioni.

Filming locations

The first scene (with the mimes acting) was filmed on the Plaza of The Economist Building (Piccadilly, London, 1959-64, project by Alison and Peter Smithson). The park scenes were filmed at Maryon Park, Charlton, southeast London, and the park is little changed since the making of the film. The street with the many maroon-coloured shop fronts is Stockwell Road, and the shops belonged to motorcycle dealer Pride & Clark. The scene where Thomas sees the mysterious woman from his car, then proceeds to follow her, was shot in Regent Street, London. He stops at Heddon Street, where the cover shot of David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust LP was later photographed.[citation needed]

Controversy

Blowup was controversial for its sexual content: it was the first British film to feature full frontal female nudity. MGM failed to obtain approval for it from the MPAA Production Code in America, but released anyway through their subsidiary Premier Productions, a key event in the Code's eventual collapse.

Awards

Academy Awards

- Nominated: Best Director - Michelangelo Antonioni

- Nominated: Original Screenplay - Michelangelo Antonioni, Tonino Guerra, Edward Bond

BAFTA Awards

- Nominated: Best British Film - Michelangelo Antonioni

- Nominated: Best British Art Direction (Colour) - Assheton Gorton

- Nominated: Best British Cinematography (Colour) - Carlo Di Palma

Cannes Film Festival

- Won: Grand Prix - Michelangelo Antonioni

Golden Globe Awards

- Nominated: Best English-Language Foreign Film

Influence

Brian De Palma's Blow Out (1981), starring John Travolta, which alludes to Blowup, used sound recording rather than photography as its central motif. In the DVD commentary to his 1974 film The Conversation, which is also about sound recording, Francis Ford Coppola said he, too, was inspired by Blow Up in writing the screenplay.

In Mel Brooks's film High Anxiety, a minor plot line involves a bumbling chauffeur who takes a picture showing the evil assassin (wearing a latex mask of Brooks's character's face) firing a gun at point-blank range at someone; he makes blow-ups until he can see the real Brooks's character, standing in the elevator in the background. (Technically speaking, the chauffeur does not make blow-ups; the joke is that he simply makes bigger and bigger enlargements until he has one the size of a wall.)

Indie filmmaker Jonathan Blitstein has said that the last scene of his 2007 film Let Them Chirp Awhile was trying to evoke the tennis ball scene at the end of Blowup. A line in the film during which actor Justin Rice as "Bobby" mentions to "Dara" played by actress Laura Breckenridge his love for the famous "tennis ball scene" was deleted from the final cut.

This film also inspired the Indian movie Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron, in which two photographers inadvertently capture the murder of a city mayor on their cameras and later discover this when the images are enlarged. The park in which the murder occurs is aptly named "Antonioni Park".

The comedy Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery features a parody of the scene in which Hemmings' character photographs a model while barking commands and voicing enthusiasm.

Peeping Tom - Michael Powell

Peeping Tom

| Peeping Tom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Michael Powell |

| Produced by | Nat Cohen |

| Written by | Leo Marks |

| Starring | Carl Boehm, Anna Massey |

| Music by | Brian Easdale |

| Distributed by | Anglo-Amalgamated Film Distributors |

| Release date(s) | May 16, 1960 |

| Running time | 101 min |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £135,000 (estimated) |

| All Movie Guide profile | |

| IMDb profile | |

Peeping Tom is a 1960 psychological thriller film by the British film director Michael Powell. The title derives from 'peeping Tom', a slang expression for a voyeur. The film is an horrific tale of voyeurism, serial murder and child abuse. The story revolves around a young man who murders women while using a portable movie camera to record their dying expressions of terror. The film was written by the World War II cryptographer and polymath Leo Marks.

Synopsis

The antagonist, Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), meets a prostitute, covertly filming her with a camera hidden under his coat. Shown from the point-of-view of the camera viewfinder, tension builds as he follows the girl into her house, murders her and later watches the film in his den as the credits roll on the screen.

Lewis is a member of a film crew who aspires to become a film-maker himself. He works part-time photographing lurid pictures of women. He is a shy, reclusive young man who hardly ever socializes outside of his workplace. He lives in his father's house, leasing part of it and acting as the landlord, while pretending to be just another tenant. Mark is fascinated by the boisterous family living downstairs and especially by Helen (Anna Massey), a vivacious sweet-natured girl who pities him. A friendship deepens into a serious relationship between them.

Mark reveals to Helen through home movies taken by his father (played by director Powell in a cameo) that, as a child, he was used as a guinea pig for his father's psychological experiments. Mark's father would study his son's reaction to various stimuli, such as lizards he put on his bed and would film the boy in all sorts of situations, even going as far as recording his son's reactions as he sat with his mother on her deathbed. The father, whose studies made him a respected psychologist, was interested in studying fear and the nervous system. He kept his son under constant watch and even wired all his rooms so that he could spy on him.

Mark arranges with Vivian (a stand-in at the studio) to make a film after the set is closed. He kills her and stuffs her into a prop trunk. The body is discovered later by the horrified film crew. The police link the two murders and notice that each victim died with a look of utter terror on her face. They interview everyone on the set and become suspicious of Mark, who has his camera always running, always recording and who claims that he's making a documentary.

A psychiatrist, called to the set to console the upset star of the movie, chats with Mark and tells him that he is familiar with his father's work. The psychiatrist relates the details of the conversation to the police, noting that Mark had 'his father's eyes.'

Mark is then tailed by the police who follow him to the building where he takes photographs of the pin-up model Milly played by real life glamour queen Pamela Green. Two versions of this scene were shot, one less risqué than the other. The more risqué scene is credited as being the first female nude scene in a major British feature. Mark kills his victim Milly and then heads home.

Helen, who is curious about Mark's films, finally runs one of them. She becomes visibly upset and frightened when he catches her. Mark reveals that he makes the movies so that he can capture the fear of his victims. He has mounted a round mirror atop his camera, so that he can capture the reactions of his victims as they see their impending deaths.

The police arrive and Mark realizes that he's finished. As he had planned from the very beginning, he impales himself with a knife attached to one of the camera's tripod legs, killing himself the same way he dispatched his victims, and with the camera running, becomes the final part of his own documentary.

Themes

Peeping Tom has been praised for its psychological complexity.[1] On the surface, the film is about the Freudian relationship between the protagonist and his father and the protagonist and his victims. However, several critics argue that the film is as much about the voyeurism of the audience as they watch the protagonist's actions. For example, Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, states that "The movies make us into voyeurs. We sit in the dark, watching other people's lives. It is the bargain the cinema strikes with us, although most films are too well-behaved to mention it."[2] In this reading, Lewis is an allegory of the director of a horror film. In horror movies, the directors kill victims, often innocents, to provoke responses from the audiences and to manipulate their responses. Lewis records the deaths of his victims with his camera and by using the mirror and showing each of his victims their last moments, provokes their own fear even as he kills them. Martin Scorsese, who has long been an admirer of Powell's works, has stated that this film, along with Federico Fellini's 8½, contains all that can be said about directing.

Responses

Peeping Tom was an immensely controversial film on initial release and the critical backlash heaped on the film all but finished Powell's career.[3] However, the film earned a cult following, and over the last thirty years has received a critical reappraisal that not only salvaged Powell's reputation but also earned the film a re-evaluation. He noted ruefully in his autobiography, "I make a film that nobody wants to see and then, thirty years later, everybody has either seen it or wants to see it."

Today, the film is considered a masterpiece and one of the best British horror films: in 2004, the magazine Total Film named Peeping Tom the 24th greatest British movie of all time[citation needed], and in 2005, the same magazine listed it as the 18th greatest horror film of all time.[4]. It was included in a BFI poll for the best British films of all time. The film was listed at #38 on Bravo Channel's 100 Scariest Movie Moments.[5] Roger Ebert has included it in his 'Great Movies' column.[6]

Relationship with Hitchcock's films

The themes of voyeurism in Peeping Tom are also explored in several films by Alfred Hitchcock. In his book on Hitchcock's 1958 film Vertigo, Charles Barr points out that Vertigo's title sequence and several shots seem to have inspired moments in Powell's film.[7]

Chris Rodley's documentary A Very British Psycho (1997) draws comparisons between Peeping Tom and Hitchcock's Psycho; the latter film was released in June 1960, only three months after Peeping Tom's premiere. Both films feature atypically mild-mannered serial killer protagonists who are emotionally obsessed with their parents. However, despite containing similarly disturbing material to Peeping Tom, Psycho became a box-office success and only increased the popularity and fame of its director. One reason suggested in the documentary is that Hitchcock, seeing the negative press reaction to Peeping Tom, decided to release Psycho without a press screening.[8]

It should be noted that Powell in his early career worked as a stills photographer and in other positions on Hitchcock's films and the two were friends throughout their careers.